This is Part 2 of a 3-part series on Chris Hani — a revolutionary, a political icon, and a contested memory in South Africa. Read Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

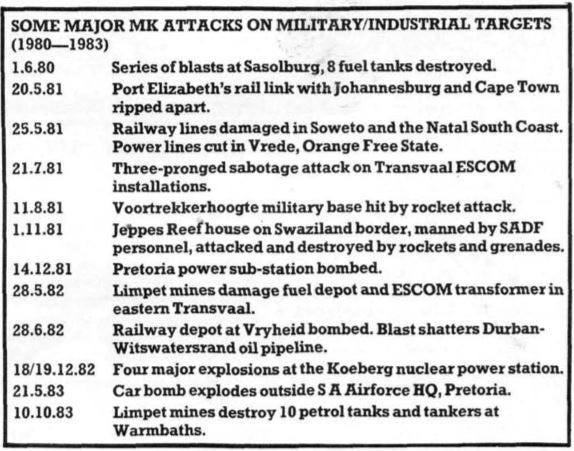

Ever since the ANC adopted armed resistance and tactics that could be classified as terrorism, the movement began to approach its political goals more seriously.

The apartheid system had been so effective at compartmentalizing the conflict that a full-scale war could rage in the townships—and the white middle class would only learn about it from the newspapers.

Hani argued that the war had to reach the white suburbs:

“We say we are fighting a civil war, but only Black people see it. (...) Very few whites have seen its reality, unless it was on TV.”

Peaceful South Africa… For the whites

That sentiment reveals a great deal about the later myth of “peaceful apartheid-era South Africa”—which, for white communities, was largely true. The country was so divided, and they were so isolated that they were not affected by violence.

But it was white South Africans whose votes kept the system in place. To create political pressure, the conflict had to enter their neighborhoods.

Because votes mattered.

South Africa regularly held elections, and for decades, the National Party (NP) kept winning. Between 1953 and 1989, the NP received more votes than any opposition party—and often several times more. In many of those elections, the main opposition didn’t question apartheid itself, but only its scale and implementation.

Apartheid was an oppressive regime, but it endured because white citizens repeatedly chose it at the ballot box.

And yet, violence under apartheid affected mostly non-whites.

Hani saw this as a reason to call for escalation.

Still, some of his statements—especially in the 1980s—revealed controversial views.

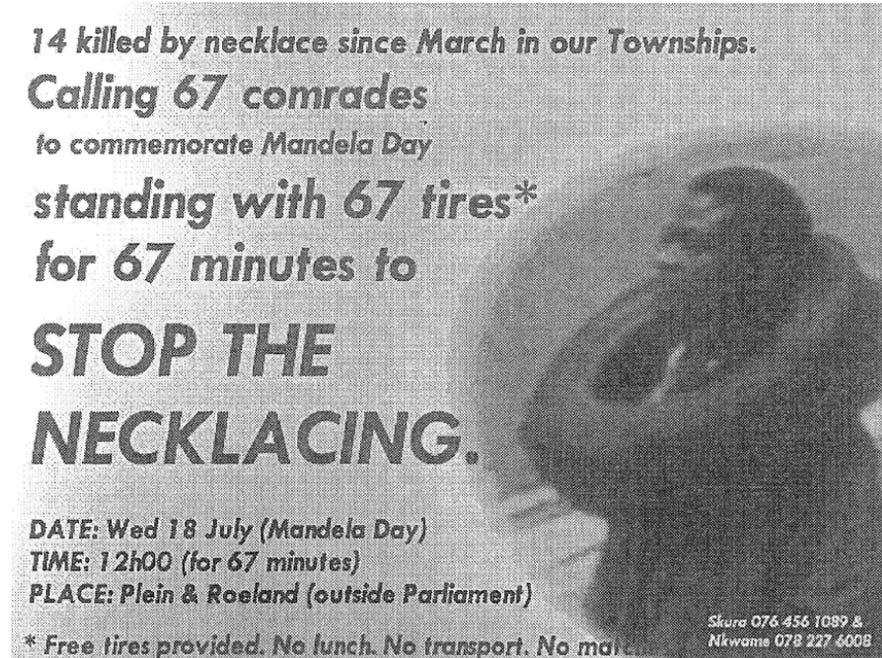

In one interview, he refused to condemn "necklacing"—a method of executing suspected apartheid collaborators by placing a petrol-soaked tire around their necks and setting it alight.

The problem was, so-called "collaborators" could be Black township police officers, or simply people accused of being informants.

Hani also challenged conventional concepts of justice, dismissing them as instruments of class oppression. He supported the idea of people's tribunals.

The Return

In 1990, Chris Hani returned to South Africa.

Two years later, he stepped down from his role in MK to focus on rebuilding the South African Communist Party (SACP).

He was seen as the only person with enough credibility to command obedience from armed youth groups in the townships—places where, in reality, civil war was already underway.

But above all, Hani was a leader who could mobilize the youth.

When Nelson Mandela sat down to negotiate with the apartheid government (a move Hani supported, even though he wasn’t directly involved), many young Black South Africans feared betrayal. For them, Chris Hani was their voice.

That may be why South Africa’s far right saw him as such a dangerous figure.

Hani believed that the liberation movement needed to maintain the support of the youth. And to do so, it had to preserve the image of defenders, not dealmakers.

“If in this cause I have to be regarded as a radical, so be it. History will judge me.”

That said, by the early 1990s, Hani was actively encouraging political participation and moving away from armed struggle—even as he remained skeptical of the apartheid regime’s intentions.

Chris Hani became—and remains—a symbol of resistance on behalf of South Africa’s poorest citizens.

During the peace negotiations, he advocated for strengthening the state and protecting the interests of the majority.

Today, we would likely describe many of his demands as socialist.

He may have been a socialist, even a communist—but he was not a Black nationalist. He supported the creation of a multiracial South Africa.

But he did not live to see that future.

The Assassination — and the Myth That Followed

A member of the Conservative Party—a right-wing splinter from the NP that rejected any reform—named Clive Derby-Lewis concluded that Hani’s death could derail the negotiations. He developed a plan and provided a weapon.

The assassin was Janusz Waluś, a Polish immigrant.

There are many theories about what would have happened had Hani lived.

Some suggest he could have triggered a civil war, or challenged Mandela's leadership. That his death, paradoxically, allowed peace to prevail.

But in fact, his murder was intended to destroy the peace process, not protect it.

And it failed.

Nelson Mandela rose to the occasion.

Those who knew Chris Hani dismiss the conspiracy theories with a smile. Mandela and Hani were not openly in conflict, each spoke of the other's importance.

And besides—Mandela managed to negotiate with people who had murdered his family. Would he not have been able to talk to Hani?

Many ANC members speak of Hani in reverent tones. He is remembered as a charismatic, extraordinary man. A natural leader.

Nomonde Kweza, a political activist who started eight community gardens in a Cape Town township, recalled organizing his speech in Lady Frere, a small town in the Eastern Cape:

“We all truly believed we had won real freedom,” she told me. “If Hani had lived, he would never have allowed inequality to grow so extreme in South Africa. After his death, many of the ideals we fought for were betrayed.”

A few years ago, President Cyril Ramaphosa said of him:

“He was a unifier—but above all, he was a nation builder.”

☕ Journalism, storytelling, fact-checking — and writing this on the side — takes caffeine. If you’d like to help fuel the next one, buy me a coffee.