Chris Hani. Part 2: The Armed Struggle

Part two on Chris Hani, a South African political icon and far-right villain

This is Part 2 of a 3-part series on Chris Hani — a revolutionary, a political icon, and a contested memory in South Africa. Read Part 1 here.

In 1961, over a year after the Sharpeville Massacre, the African National Congress formed its armed wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe. ANC leaders decided that the organization had to be capable of waging armed struggle.

Among its founders was Nelson Mandela.

Chris Hani joined uMkhonto we Sizwe when he was nineteen years old.

He would later recall that joining MK marked the beginning of his involvement in the armed struggle. He emphasized, however, that he never saw violence as the only method of resistance—it was just one element in a broader campaign.

Soon after joining uMkhonto we Sizwe, Hani was arrested for the first time. He was stopped at a roadblock and jailed under a law that allowed the government to detain "subversives" for up to 90 days without trial.

Ironically, the reason for his arrest was the possession of propaganda materials criticizing those very laws.

That moment placed Hani squarely in the crosshairs of the apartheid security services—but also marked his entry into the ranks of the ANC’s most serious underground activists.

Not long afterward, he was arrested again—this time receiving a sentence of one and a half years.

During a temporary release from prison, Hani went underground.

A Trip to the Soviet Union

Intelligent, educated, and from a politically engaged family, he quickly attracted attention among ANC leadership.

A year later, he left South Africa as part of a group of thirty MK members traveling to the Soviet Union, where he underwent training in armed struggle and intelligence.

The fascination of African Black militants with the USSR was hardly unusual.

First, the Soviet Union supported them materially and militarily. Second, for many, the contrast was jarring: they went from being second- or third-class citizens in their own countries to honored guests in Moscow or Tashkent.

They received training, uniforms, respect—and were spared the realities of Soviet life, while benefiting from its resources.

It was, however, only the beginning of an exile that would last many years.

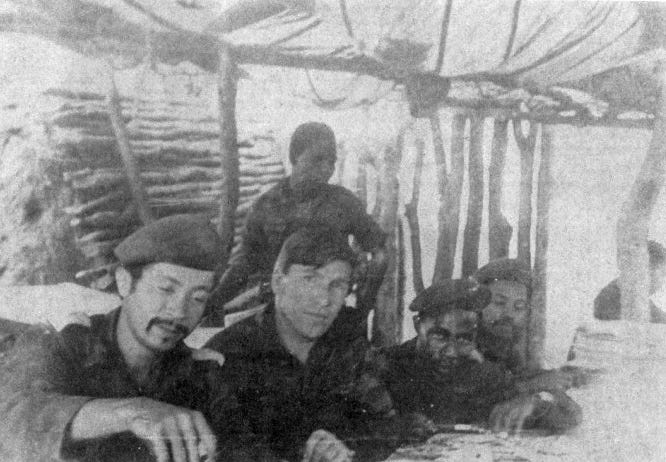

Hani’s next station was the Second Chimurenga—the war for Zimbabwean independence, often called a civil war.

The military campaign he participated in ended in defeat. But in a conflict between a mostly white minority regime and the impoverished Black majority, the real gains were political and symbolic rather than military.

It was during this conflict, and in particular after being taken prisoner, that Hani began to radicalize—but his radicalism was not directed at the enemy, but at his own party.

After being released from captivity, Hani and several others co-wrote the Hani Memorandum.

This document remains a fascinating political artifact.

Criticizing ANC and “not opposed to executions”

In the Memorandum, Hani and his co-authors harshly criticized the ANC leadership. Instead of focusing on the liberation struggle, they argued, the party had become bloated and self-serving.

The memorandum noted that the ANC had taken over the furniture industry in Lusaka, that senior officials enjoyed luxury cars and high-end medical care—perks unavailable to rank-and-file members.

The authors accused the leadership of "flirting" with the Peace Corps and with Israeli companies—entities they considered tools of the CIA and the Israeli Shin Bet.

They wrote that they were “not opposed to executions of traitors,” but demanded transparency, trials, and even—ironically—adherence to human rights standards. They listed several cases in which accused traitors within the ANC had been treated “inhumanely.”

The scandal sparked by the Memorandum led to the 1969 Morogoro Conference, during which the ANC underwent significant internal reforms. However, the conference also reinforced a key principle: it was the ANC politicians who ruled the army—not the other way around.

The conference introduced one other major shift: The ANC would now admit non-Black members for the first time in its history.

This moment marked a turning point in Hani’s political identity.

He was eager to work with white comrades and belonged to the part of ANC that believed the liberation struggle was a fight against a system, not against white people themselves. He believed that the future South Africa should be based not on race, but on shared citizenship.

Hani’s commitment to working with white South Africans is only one side, though. Let’s not kid ourselves. Although Hani said he was not a butcher “like the leaders of the apartheid regime”, and that civilians were not his target, he did believe that the armed struggle had to be brought into white towns and suburbs.

“We are realists,” he said. “The theatre of these actions will be white residential areas, and it is inevitable that white civilians will die.”

This is part 2 of a 3-part series on Chris Hani, revolutionary memory, and political myth in South Africa. Subscribe to get the next chapter soon.

☕ Journalism, storytelling, fact-checking — and writing this on the side — takes caffeine. If you’d like to help fuel the next one, buy me a coffee.